The Ones Who Printed Us: A Tribute to the Magazines That Made Culture

Before hashtags and brand campaigns, a generation of now-defunct people of color led print magazines to define visibility, community, and cool. Their influence shaped more than media—it shaped identity.

The Magazines That Made Culture Before It Was Marketable

At their height, they lived in corner stores and coffee tables, under barbershop chairs and inside aunties’ tote bags. They smelled of ink and perfume samplers. Their spines curled with wear. And for those who came of age before “representation” became a digital talking point, they were something more vital: proof of life.

Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a constellation of independently run, often underfunded, but culturally seismic magazines reshaped the publishing landscape. These were publications created by and for communities of color, and they captured what mainstream media consistently ignored: the nuance, brilliance, contradictions, and style of lives lived at the intersections.

From Negro Digest to Vibe Vixen, Giant Robot to Latina, from Upscale to TRACE, KoreAm to Faces, these magazines built cultural memory in real time. They didn’t just document moments—they created them. And while many have now shuttered, their editorial DNA remains traceable across today’s fashion pages, music coverage, and digital media platforms.

This is a tribute to the fallen. To the publishers, editors, stylists, and culture workers who carved out space in print when there was none. To the legacy they left behind. And to the urgency of remembering them.

I. Revolution on the Newsstand: The Legacy of the Originals

Before the advent of digital-first media, communities of color had to look to niche publications for stories that resembled their lived experience. Negro Digest, launched in 1942 by John H. Johnson, was one of the earliest to do so. Modeled after Reader’s Digest but featuring Black voices, it offered literary essays, political commentary, and cultural criticism. The magazine featured regular contributions from Langston Hughes, Margaret Walker, and W.E.B. Du Bois.

In 1970, Johnson evolved the publication into Ebony Jr. and later Ebony and Jet—household staples that celebrated Black excellence in politics, sports, beauty, and business. With glossy covers that ranged from civil rights leaders to Motown stars, these magazines provided both aspiration and affirmation. When Ebony put a young Barack Obama on the cover in 2004, it wasn’t just reporting history—it was foreshadowing it.

Likewise, Emerge (1989–2000), often referred to as the Black Time, tackled issues of systemic injustice, economic disparity, and racial politics with journalistic rigor. Under the leadership of editors like George E. Curry, Emerge earned a reputation for hard-hitting cover stories and a commitment to truth-telling. A 1994 cover—"What’s Next for Black America?"—remains emblematic of its prescient editorial voice.

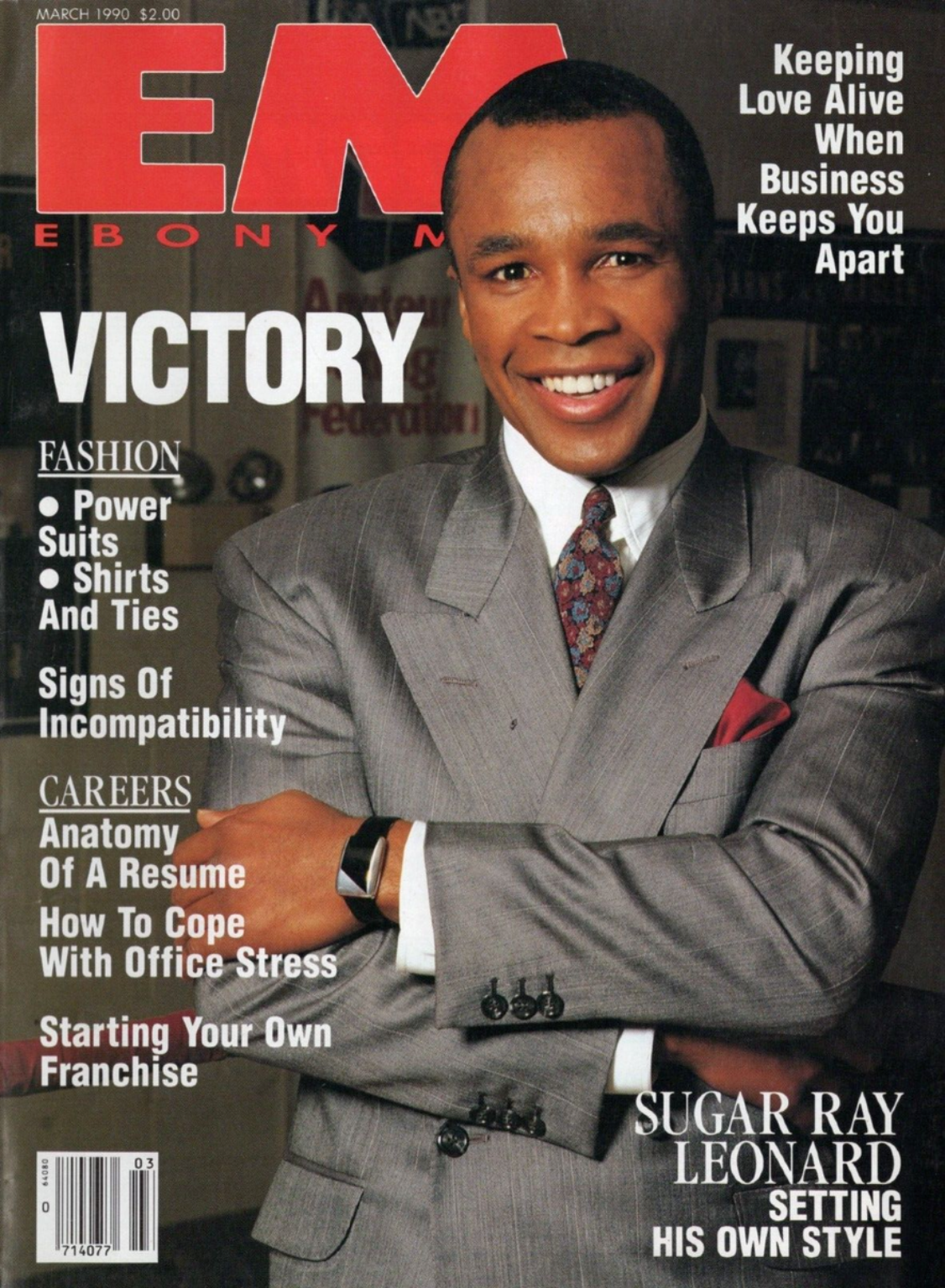

Other titles like Ebony Man (EM) and Black Stars provided gender-specific lenses within the broader Black publishing tradition, showcasing Black masculinity and celebrity through lifestyle, entertainment, and sociopolitical coverage. Meanwhile, Savoy (2001) aimed for a cosmopolitan Black male audience, blending business, style, and culture with sharp visuals and long-form features. It was GQ by and for the diaspora.

These magazines were not sole reflections of culture, but served as architects of it as well.

II. The Cool Years: Fashion, Fame, and Firsts

As hip-hop entered the mainstream and multiculturalism became a buzzword, a new generation of magazines emerged, focused on the intersections of style, celebrity, and street culture. These publications were unapologetically of the moment, speaking directly to youth who saw themselves reflected nowhere else in the media.

Honey (1999–2006) was representative of this era. With the tagline "For Women Who Are Fly, Fierce, and Fabulous," Honey featured editorial spreads on beauty, fashion, and relationships through a distinctly Black and brown lens. Beyoncé, Eve, Lil’ Kim, and Lauryn Hill all graced its pages before mainstream fashion media began to pay attention. One of the magazine’s most iconic covers featured Aaliyah in a sheer white tank top and gold hoops—a quietly radical departure from the Eurocentric glamour of Vogue. Honey’s writing was sharp, often sassy, but grounded in a respect for its readers. The magazine offered sex advice, career tips, and real talk on friendships and family, forging a sense of intimacy and trust that rivaled more established brands.

Vibe Vixen, the sister magazine to Vibe, launched in 2004 and ran until 2009. Though short-lived, it made an outsized impact. It offered a nuanced portrait of Black and Latina womanhood—interviewing stars like Ciara, Ashanti, and Gabrielle Union on their own terms. Fashion editorials juxtaposed streetwear with high fashion, while columns tackled colorism, dating, and economic independence. Vibe Vixen also took beauty seriously, foregrounding products for darker skin tones and celebrating natural hair long before it became mainstream.

Magazines like Élan, Estylo, and Urban Latino expanded this cultural lens to reflect Afro-Latino and bicultural urban life. They elevated voices from the barrio to the boardroom, mixing regional pride with global style.

Latina (1996–2018) was similarly groundbreaking. Founded by Christy Haubegger, it provided lifestyle, beauty, and political content tailored for bicultural readers. Its covers—Jennifer Lopez, Salma Hayek, and Rosario Dawson, among others—reflected a mainstream success that still felt rooted in community. Latina carved out space to talk about immigration reform, bilingual identity, and the contradictions of living between cultures. The magazine featured in-depth interviews with Latina politicians, business leaders, and creatives, alongside makeup tutorials and fashion trends tailored to diverse skin tones and body types. Complementing Latina were publications like Siempre Mujer, Loft, and Latino Perspectives, each adding texture to what it meant to navigate identity, womanhood, and aspiration en español y inglés.

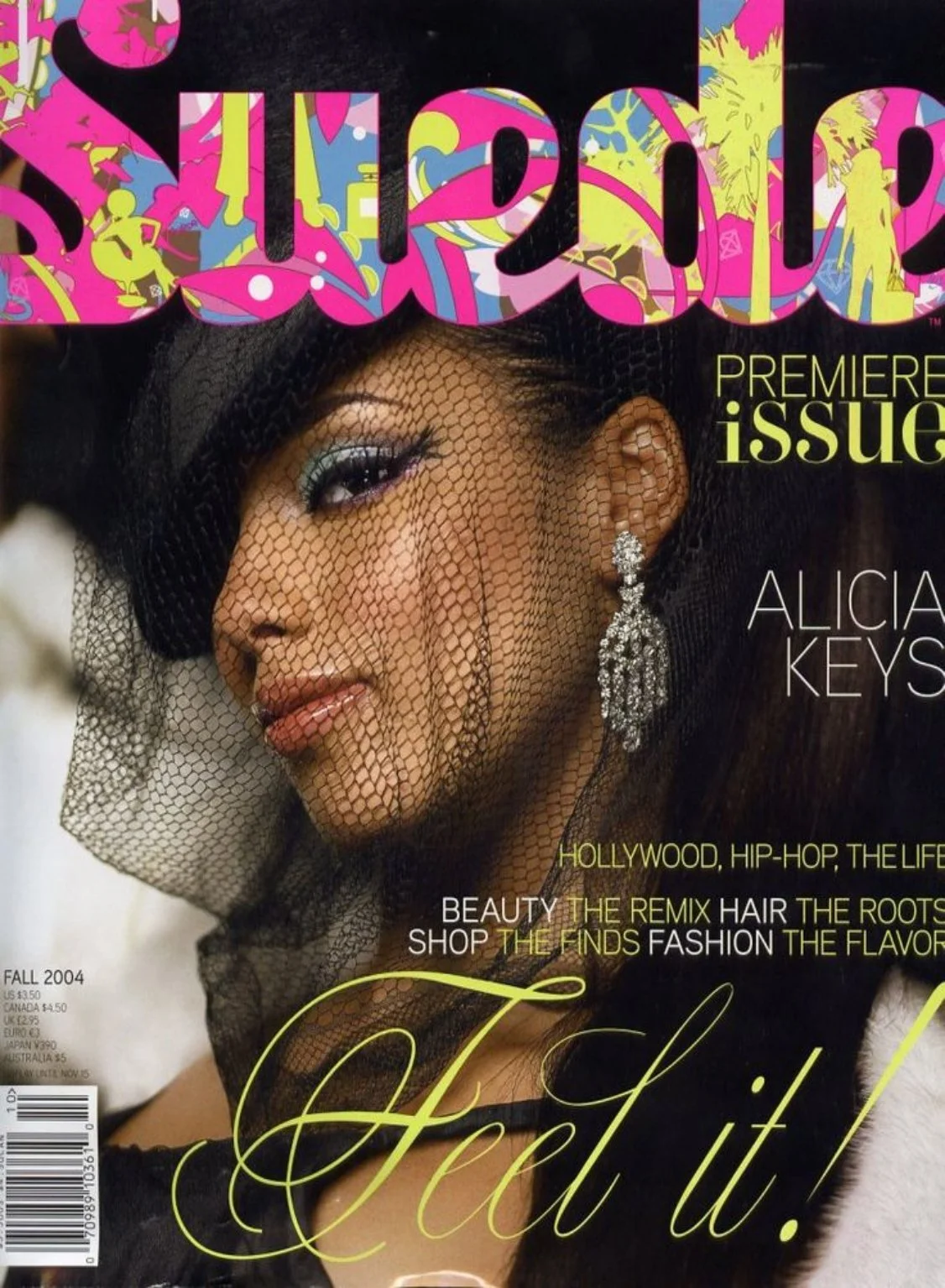

Suede, a joint venture between Essence Communications and Time Inc., also deserves mention. Though it only published four issues in 2004–2005, it made a splash with its high-end visuals and boundary-pushing content. Suede covered fashion through a distinctly Afro-diasporic lens, with shoots that blended couture and cornrows, leather and locs. Its motto—"Style, Substance, and Soul"—summed up its mission to center Black women’s aesthetics and intellect equally.

These magazines bridged commercial appeal and cultural specificity, achieving a kind of editorial alchemy that has rarely been matched since. They captured celebrities not just as stars, but as avatars of style and resistance. Their coverage was intimate, unapologetic, and rooted in community, redefining who and what could be considered aspirational in glossy pages.

III. Margins and Mastery: The Alt and Indie Presses

Beyond the glossies, an indie press boom carved out deeper, more experimental territory. These magazines weren’t trying to assimilate—they were documenting what it meant to live on the edge of multiple identities. With bold visuals, sharp commentary, and an unflinching sense of self, they turned the margins into sites of mastery.

Giant Robot, launched in 1994 by Eric Nakamura and Martin Wong, became an essential outlet for Asian American and Pacific Islander pop culture. The magazine’s eclectic range—Asian cinema, lowbrow art, designer vinyl toys, skate culture—earned it cult status. Its feature on actor Daniel Dae Kim before Lost, interviews with punk bands like The Plastics, and in-depth coverage of Japanese game developers provided a view into an underground culture that was, at the time, mostly invisible. Giant Robot also expanded into a gallery and retail space in Los Angeles, transforming the magazine into a full-fledged cultural ecosystem that bridged indie publishing and contemporary art.

Other AAPI titles like A. Magazine, AsiAm, Jade, and Transpacific provided platforms for generational dialogue, campus activism, and diasporic storytelling. Whether covering Tiger parenting myths or profiling LGBTQIA+ Asian creatives, they gave voice to a multiracial, panethnic complexity rarely seen in legacy media.

Hyphen, born out of the AAPI arts nonprofit Youth Outlook in 2003, took a more political tack. Tackling post-9/11 surveillance, anti-Asian racism, and queer identity, the publication had a zine-like defiance paired with sharp design sensibilities. Its essays were often academic-adjacent, aimed at readers who were hungry for more than assimilation narratives. Hyphen’s "Token" column dissected the complexities of racial representation in media with a wit and clarity that resonated deeply with its readership. It became a favorite among emerging AAPI creatives and activists, offering both critique and community.

Yolk (1994–2004), a lesser-known but culturally rich magazine, used humor, satire, and glossy design to engage a pan-Asian readership. It included features on AAPI musicians, chefs, and mixed-race identity, becoming a touchpoint for millennial AAPIs who had never seen themselves depicted with such complexity. Its pop culture-heavy covers—like Margaret Cho decked out in glam drag or DJ Qbert surrounded by turntables—were emblematic of its irreverent, genre-blending approach.

Even lesser-known gems like East West (by Annie Wong) and Filipinas offered community-specific journalism that resisted erasure. Whether covering politics or pop culture, their pages made Asian America visible—on its terms.

Indigenous publications like Akwesasne Notes and Indian Country Today existed alongside these titles, centering sovereignty and survival in a publishing world that often marginalized Native voices. Akwesasne Notes, published by the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs from the late 1960s onward, functioned as a transnational newsletter for Indigenous resistance, reporting on land struggles, treaties, and environmental justice. Indian Country Today, which continues today in digital form, chronicled legal battles, tribal governance, and the lived realities of Native communities with journalistic rigor and cultural specificity.

For Latino communities, Latina magazine (1996–2018) carved out a glossy niche, but titles like loquéno, ConSafos, and Fuego captured more subversive and radical voices. These outlets documented the Latino art movement, bilingual poetics, and urban politics with a literary and visual flair rarely seen in mainstream platforms.

These publications weren't "alternative" by choice—they were by necessity. Their vision wasn’t limited to survival; it was expansive. They offered editorial blueprints for identity without compromise, embracing contradiction and complexity, and leaving behind a body of work that continues to inform and inspire.

Magazines like Open Your Eyes, Nuestro, and Hispanic carved out space for Latino voices often erased from mainstream narratives, documenting urban life, activism, and culture from New York to Los Angeles.

IV. Beauty, Belonging, and Soft Power

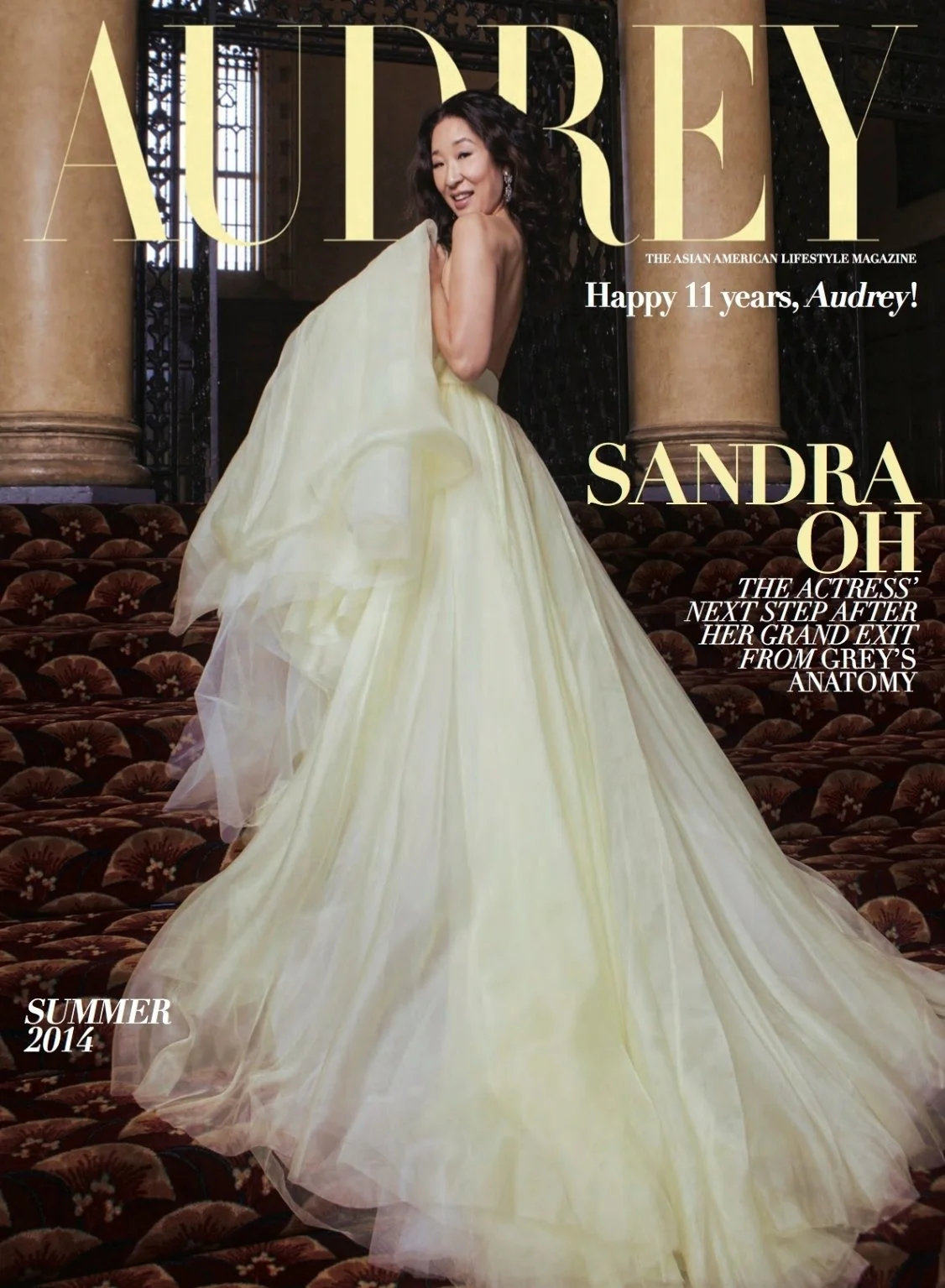

If the cool magazines were about visibility, these were about interiority. Audrey (2003–2015) and Black Elegance (1990s–2000s) used fashion, food, and lifestyle content as a gateway to deeper cultural commentary.

Audrey, an AAPI women's magazine named after the publisher’s daughter, dedicated space to beauty tips and celebrity profiles while also publishing essays on intergenerational trauma, body image, and mental health. It was among the first to spotlight Asian American creatives and influencers before influencer culture had a name. Cover stars included actresses like Lucy Liu Sandra Oh, and Maggie Q, while the back pages often featured reflective pieces on filial piety, immigrant motherhood, and the politics of Asian beauty standards—from skin whitening to eyelid surgery. In doing so, Audrey validated the layered identities of its readership, offering both glamour and emotional nuance.

Black Elegance, with its lush photography and elegant layouts, offered an aspirational vision of Black luxury. Coverage of events like the Bronner Bros. Hair Show and features on Black interior designers, chefs, and aesthetes created a quiet but powerful portrait of what refined Black life could look like. The magazine often centered weddings, galas, and home tours, signaling that style and sophistication belonged as much to the Black experience as resilience and protest. Advertisements were tailored to Black-owned beauty brands and luxury products, a deliberate economic intervention that challenged assumptions about what Black consumers wanted or could afford.

Similarly, Today’s Black Woman and Sister 2 Sister catered to the intimate aspects of Black life. The former offered essays on spirituality, wellness, and community leadership, while the latter became a go-to for celebrity gossip with a soulful twist—combining pop culture with kitchen table candor.

Together, these magazines redefined what power could look like on the page. They challenged the notion that identity had to be hard-edged to be valid, or that cultural commentary had to come cloaked in critique. In centering softness, family, wellness, and taste, they modeled a quieter form of resistance—one that claimed space for joy, beauty, and belonging. At a time when the dominant narratives of racialized life were rooted in struggle, these publications insisted that care and aesthetics were also political.

Across all these publications—from the sleek spreads of PODER360 to the glossy ambition of Giant magazine—identity was never just an aesthetic. It was always a politic, shaped by who had the mic and who dared to pass it.

This ethos reverberates in today’s digital spaces—from Instagram pages dedicated to Asian skincare rituals to TikToks of Black homemaking influencers. The soft power once held by Audrey and Black Elegance laid the groundwork for how identity, taste, and self-expression now unfold across platforms. Their legacy isn’t just visual; it’s philosophical.

V. Why They Vanished—and Why They Still Matter

For all their brilliance, most of these publications couldn’t withstand the combined pressures of digital disruption, limited advertiser support, and institutional neglect. Unlike mainstream titles buoyed by conglomerate funding, magazines that were run by editors of color often operated on razor-thin margins, dependent on community goodwill and passion.

Some failed not due to lack of creativity or cultural relevance, but because of financial mismanagement and a lack of infrastructure—a challenge endemic to the industry, but especially unforgiving for independent titles. Honey, as mentioned, was one of the most beloved Black women's lifestyle magazines of the early 2000s, folded not simply due to external pressures, but from internal financial missteps. In an interview with Essence writer Keyaira Boone, former editor Kierna Mayo reflected that the absence of a solid business foundation made it difficult for Honey to compete or sustain itself long-term, even though it had captured a fiercely loyal audience and tapped directly into the zeitgeist. It’s a cautionary tale that’s echoed across the publishing world: editorial brilliance alone isn’t enough.

When Condé Nast folded Teen Vogue’s print edition but doubled down on digital, it signaled a pivot the indie press couldn’t match at scale. Print advertising declined. Distribution became harder. Talent moved to corporate roles for survival. And the communities these magazines served were often the last to be considered viable markets by traditional investors.

Now, with the rise of AI and automation, media as a whole is facing an existential reckoning. The platforms that once promised democratized storytelling are increasingly shaped by algorithms and generative content. For many, tech—not culture—is the new It Girl. Writers are pivoting to prompt engineering. Journalists are becoming creators. Outlets are consolidating or collapsing. And the conditions that once made room for small, culture-driven magazines are now harder than ever to recreate. The editorial voice of gal-dem, the aesthetic of TONAL, the archival impulse of Archivistas, the radical softness of Substack newsletters by queer writers of color—all trace roots back to Jet, Sister 2 Sister, loquéno, and America (the early 2000s version helmed by Smokey D. Fontaine), which redefined cool from the margins.

Yet their legacy endures. The editorial voice of gal-dem, the aesthetic of TONAL, the structure of Substack newsletters by writers of color—all trace roots back to these print pioneers. Their work seeded a generation of editors, stylists, writers, and readers who carry forward their spirit in newer, more nimble forms.

Eternal proof that representation, when done right, leaves a mark that never fades.