Aesthetic Expression: Nicholas Galanin Reimagines Land, Sovereignty, and Survival

On the western edge of Alaska, surrounded by dense forests and the endless stretch of water that marks Lingít Aani (Tlingit land), Nicholas Galanin carves space for visions that are at once ancestral and urgent, poetic and unflinching. A Lingít/Unangax̂ multi-disciplinary artist, Galanin has spent over two decades creating work that cannot be neatly categorized: he moves fluidly across sculpture, video, installation, music, jewelry, and performance. His practice is not simply about aesthetics—it is about survival, sovereignty, and the enduring presence of Indigenous knowledge.

“I am inspired by generations of Lingít & Unangax̂ creative production and knowledge connected to the land I belong to,” Galanin writes in his artist statement. “From this perspective I engage across cultures with contemporary conditions.” That insistence—rooting the present and the future in inherited forms of knowledge while refusing containment—is what makes Galanin one of the most vital contemporary artists working today.

A Practice Without Boundaries

Born in 1979 and raised in Sitka, Alaska, Galanin comes from a lineage of master carvers and jewelers. His formal education spans London Guildhall University, where he studied silversmithing and jewelry design, and Massey University in New Zealand, where he earned an MFA in Indigenous Visual Arts. But perhaps most formative was his traditional apprenticeship with carvers and cultural leaders in his community—a training that embedded him in both technique and responsibility.

This hybrid education—community apprenticeship, academic rigor, and international exposure—set the stage for a practice that resists binaries. He uses Indigenous and non-Indigenous materials, draws on customary forms and experimental technologies, and brings together political critique with lyrical abstraction. The result is work that feels grounded in tradition while radically contemporary.

Over the years, his art has ranged from masks cut out of anthropological texts to petroglyphs etched into coastal rocks and sidewalks, from tourist-shop carvings splintered and rearranged to a taxidermied polar bear collapsing into its own fur. Each piece interrogates how histories of commodification, extraction, and erasure have warped our understanding of culture and land—and how art can counter such narratives.

Excavating Shadows, Reclaiming Land

Two of Galanin’s most widely recognized works exemplify his ability to intervene in public space with both subtlety and force.

In 2020, at the Biennale of Sydney, he excavated the shape of the shadow cast by the statue of Captain James Cook in Hyde Park. Instead of a monument celebrating colonization, the negative space left in the ground transformed into a call to bury—not revere—such figures. It was an act of visual absence that spoke louder than any toppled statue: a critique of anthropological bias and a reminder of what colonization sought to erase.

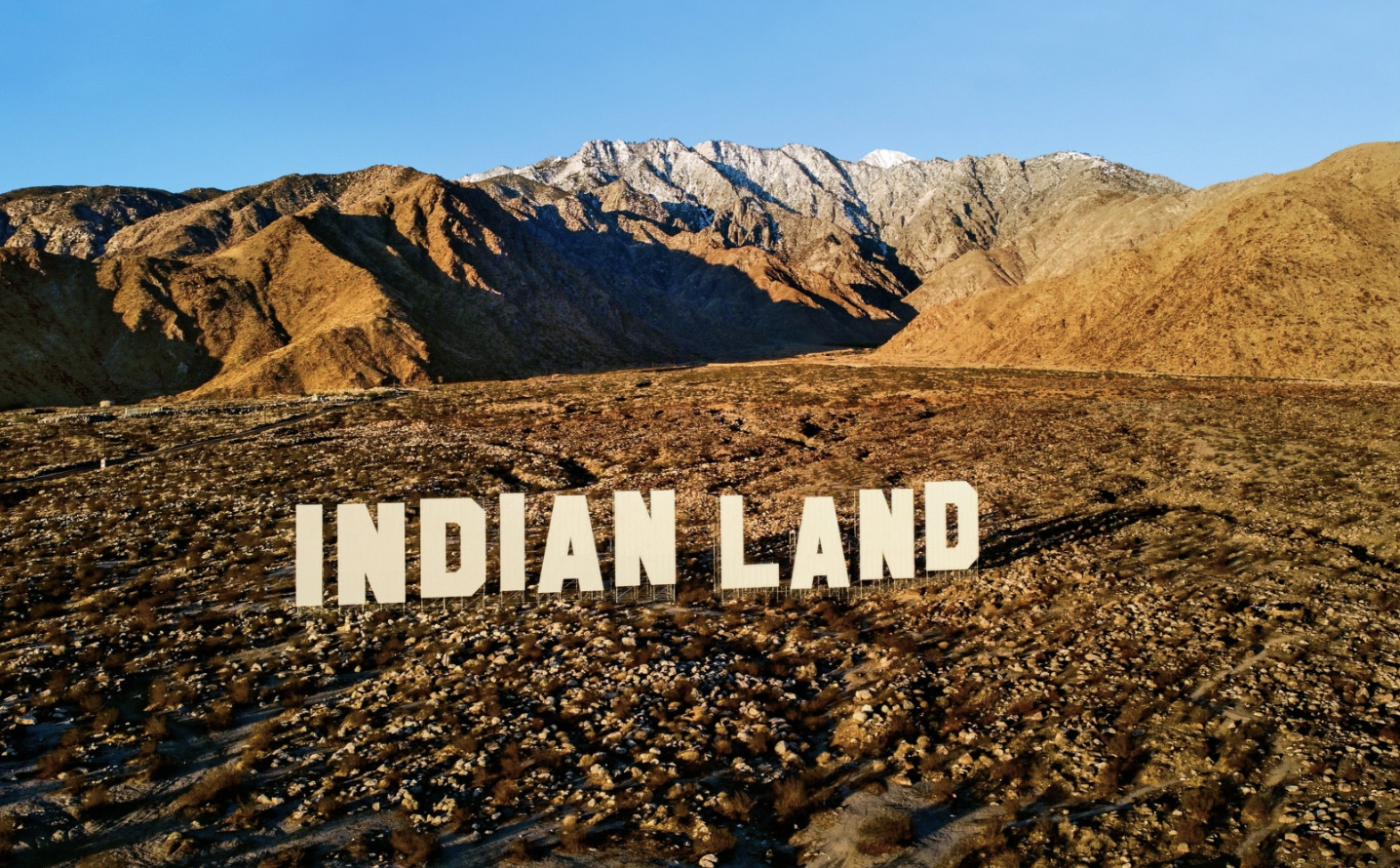

The following year, for Desert X in Palm Springs, Galanin recreated the Hollywood sign—but instead of the iconic letters spelling out the entertainment capital, his installation declared: INDIAN LAND. Visible from miles away, the work directly supported #LandBack and real rent initiatives, making visible the enduring claims of Indigenous people to the very ground beneath America’s mythologies of fame and success.

These interventions embody Galanin’s philosophy: art as both critique and affirmation, a vessel for cultural resurgence as much as for dismantling structures of erasure.

Refusing Romanticization

Central to Galanin’s practice is a refusal to let Indigenous art be confined to stereotypes—whether of timeless craft, anthropological specimen, or commodified souvenir. “I resist romanticization, categorization and limitation,” he writes. His works are not nostalgic gestures toward a past culture; they are active engagements with living traditions and living communities.

This resistance is evident in his treatment of materials. He has splintered mass-produced carvings meant for tourists, reassembling them to reveal the damage of commodification. He has made contemporary jewelry that nods to customary form while carrying pointed political critique. He has turned anthropological texts—the very books that once classified and constrained Indigenous lives—into objects of reimagined meaning.

What emerges is not simply a rejection of the colonial gaze but an articulation of Indigenous sovereignty through aesthetics. Galanin’s work asserts that difference is not a weakness to be assimilated away, but a strength to be celebrated.

Between Art and Music

Though best known for his visual practice, Galanin’s creative work also extends into sound. He records music under the label Sub Pop, weaving sonic landscapes that, like his visual art, resist easy classification. For Galanin, music is another vessel—a way to carry memory, emotion, and resistance across mediums.

His presence featured on platforms like YouTube and Spotify broadens his audience, bringing listeners into the orbit of his vision in yet another form. In a world where artists are often pressured to specialize, Galanin’s refusal to choose between disciplines is itself a statement: culture, like land, “cannot be contained.”

Recognition and Reach

The art world has taken notice. Over the past decade, Galanin has exhibited internationally—from the Whitney Biennial in New York to the Venice Biennale, from Toronto Nuit Blanche to the Honolulu Biennial. His solo exhibitions have stretched from Anchorage to Vancouver, from Baltimore to Boston.

In 2025, his exhibition Aáni yéi xat duwasáakw (I am called Land) opened at the Massachusetts-based MAAM, continuing his interrogation of land and sovereignty. That same year, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Alaska Anchorage—just one of many accolades in a career that includes a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Joan Mitchell Fellowship, and the Soros Fellowship.

His work resides in the collections of major institutions worldwide: the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa), the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery, and many more. Yet despite this global recognition, Galanin continues to live and work with his family on Lingít Aani in Sitka, Alaska.

An Intellectual Edge

What distinguishes Galanin is not just his technical mastery across disciplines, but the clarity and sharpness of his thought. His works are, as he describes them, “vessels for knowledge, culture and technology— inherently political, generous, unflinching, insistent and poetic.”

In a contemporary art world often preoccupied with spectacle or market value, Galanin insists on depth. His pieces demand context, history, and intellectual engagement. They cannot be reduced to decorative objects. They are questions posed to viewers: What histories do we inherit? What violences are buried in plain sight? What futures can we imagine if we center Indigenous knowledge?

Looking Forward

For Galanin, the work is never static. Each exhibition is part of a larger pursuit of freedom and vision for both present and future. His community projects—such as carving totem poles, dugout canoes, and healing poles for Tlingit families and public institutions—reflect his belief that art should not only reside in museums but also in living community spaces.

As climate change, political unrest, and cultural erasure continue to shape our world, Galanin’s art reminds us of resilience, adaptation, and resurgence. His practice is not about preserving tradition in amber but about carrying it forward—reshaped, reimagined, and insistent on survival.

Let’s Reflect

Nicholas Galanin’s work refuses easy consumption. It asks more of us: to look beyond the surface, to interrogate the systems we take for granted, and to see land, culture, and sovereignty not as abstract ideas but as lived realities.

“I use my work to explore adaptation, resilience, survival, active cultural amnesia, dream, memory, cultural resurgence, connection to and disconnection from the land,” he writes. In this, Galanin is not only an artist but a storyteller, a critic, and a visionary.

In a time when art can too often be reduced to commodity or spectacle, Galanin reminds us of another possibility: art as vessel, as refusal, as future.

You can find more of Galanin’s work here.